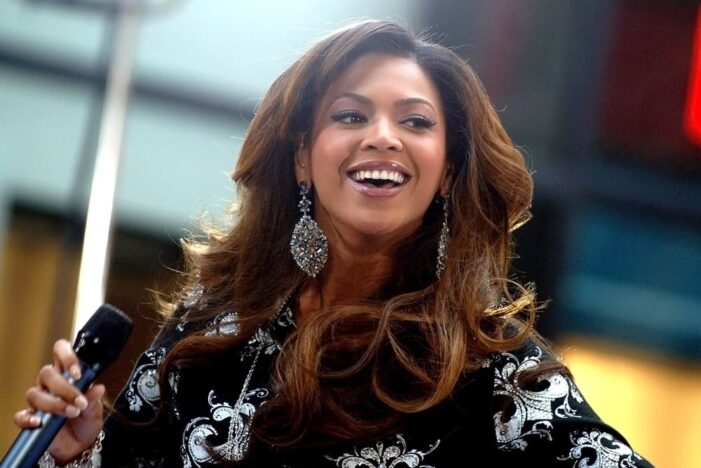

Editorial credit: Everett Collection / Shutterstock.com

By Kimberly Bryant | MSN

“Hers was not a voice or a face to forget. Yet, we forgot.” Those words by Alice Randall reflected the nearly lost legacy of Linda Martell, the first Black woman to top the country charts. Her reflection is a warning not to repeat history now that Beyonce has ascended to the top of those same charts.

Beyonce’s presence in country music is not an anomaly; it symbolizes a collective reclamation of a shared legacy and an indictment of the systemic marginalization of Black women in country music. Even more importantly, it forces us to confront the reality of whose contributions get remembered and who gets overlooked.

When Beyoncé released her two new singles, “16 Carriages” and “Texas Hold’ Em,” I felt transported back to the Tennessee of my childhood. In that place, we reserved Saturday afternoons for “Hee Haw,” a country music television show that, while entertaining, did not adequately reflect the diversity fundamental to the genre’s birth. We reserved Saturday evenings to enjoy the trailblazing R&B television show “Soul Train.” We spent Sunday mornings immersing ourselves in Sunday school and the music of our Missionary Baptist gospel hymns and choirs.

I am a daughter of the South, where the twang of country music intertwines with the soulful longings of the Delta Blues and the passionate orations of the Southern Baptist sermons that shaped my youth. Surely, blues, soul, R&B, and gospel music pervaded my life growing up in the urban landscape of a very Black Memphis.

Girls like Linda Martell, Beyonce, and I may not fit the typical image of a “country girl,” but that doesn’t mean country music doesn’t “move” us. It does, and we belong to it. When Linda Martell dropped her first and only country album in 1969, the establishment finally cracked open its doors for Black girls.

Martell’s arrival on the country scene was dynamic but brief. She released her album Color Me Country to much excitement, and it even broke into the country music charts. During her in-person appearances, country music fans were taken aback to witness a young Black woman with the melodic voice they had enjoyed on the radio instead of the blonde white icons they were accustomed to seeing on these stages.

These crowds heckled her during performances and complained to promoters about the invasion of a previously lily-white space. She would perform at the Grand Ole Opry several times and even occasionally appeared on “Hee Haw”–a rare appearance for a woman of color. But eventually, her career vanished into the annals of musical history.

Despite this erasure, Martell left an indelible mark on many of country music’s contemporary stars, such as Mickey Guyton, Rissi Palmer, Ruby Falls, and Rhiannon Giddens. Rissi Palmer’s podcast “Color Me Country” pays homage to Martell’s groundbreaking album in its title and content, which celebrates the artists of the past and highlights Black, Latinx, and Indigenous musicians shaping the genre today. These artists have left a unique mark on the country music scene, bringing their talents to some of the most revered stages in Nashville and abroad. They are movers, shakers, trailblazers.

They have also experienced some of the same challenges she did, such as limited access to and play on country music stations, minimal elevation on large platforms for visibility and reach, and major hurdles to artist deals and securing contracts to help their work scale and grow.So what’s changed for Black women in country music in the 55 years since Martell’s album?

There are certainly more recognizable Black women country music artists on the airways and stages now than there were in Martell’s day. For example, Country Music Television (CMT) programs, such as Next Women of Country and the Equal Play Award hosted by Leslie Fram, helped increase opportunities and bring attention to an emerging cohort of Black women in country music. But to be clear, the progress made is still insufficient.

Only seven Black women have reportedly charted on the Billboard Country Charts over the past 50 years, and only five Black women have either written or co-written a #1 Billboard Country song in that same time frame.

As an art form with roots in the folk music traditions of early European immigrants whose fiddle styling melded with the soulful rhythms of the banjo–a staple transported to America’s shores by enslaved Africans–one would expect Black artists to enjoy more presence and cultural ownership in this quintessentially American art form. Yet this is not the case. It’s far from it.

Despite her unprecedented success and undeniable star power, Beyoncé’s venture into country music hasn’t been devoid of challenges. During a 2016 CMA performance of ‘Daddy Lessons’ alongside the Dixie Chicks, the crowd reacted poorly, and the network cut the performance from the recorded broadcast. More recently, Oklahoma’s country radio station KYKC refused to play ‘Texas Hold’ Em’ until fans protested.

In an Instagram post reflecting on her journey ten days before her new album dropped, Beyoncé shared, “This album has been over five years in the making.It was born out of an experience that I had years ago where I did not feel welcomed…and it was very clear that I wasn’t.” Her words highlight not just the personal adversities she faced, but also her relentless pursuit of artistic authenticity and freedom of expression.

Beyoncé’s deep dive into the roots of country music, driven by an unwelcoming experience, mirrors the broader narrative of Black women in this industry and others—navigating spaces where their presence is questioned, yet their influence is undeniable.

This pushback, even for the world’s biggest pop music star, angers me. There is an endemic practice afoot. The erasure of the legacies and stories of Black women is prevalent in many spaces. We are easily forgotten. It takes resilience, talent, and a deep understanding of one’s heritage to push through these barriers. I call this the Black Girl Boss Paradox: the contradiction by which Black women are celebrated for their talents, strength, and leadership capabilities—often being hailed as trailblazers or saviors in times of crisis—while simultaneously facing systemic barriers, scrutiny and underestimation of their abilities.

I have spent decades building my career in spaces where there were few people who looked like me, and I have witnessed the blatant attempts to erase the accomplishments of Black women. People remove histories from webpages and periodicals, leave contributions uncited or unrecognized, and take accomplishments from us and give them to others.

Beyoncé’s resolve to “propel past the limitations that were put on me”and her commitment to blending genres on her own terms crystallizes the essence of what it means to challenge and redefine boundaries. Her determination and the subsequent success of “Act II” illustrate the Black Girlboss Paradox, showing how these moments of backlash aren’t just isolated incidents; they’re manifestations of a broader systemic effort to minimize and erase the contributions of Black women.

Martell’s pioneering presence at the Grand Ole Opry and Beyoncé’s recent chart-topping success are milestones. Yet, they spotlight the paradoxical reality: we celebrate these women for their resilience and innovation, but they navigate a landscape riddled with skepticism, underestimation, and marginalization. This contradiction confronts Black women leaders and creatives across all sectors, not just in country music.

There are many ways to forget “us .”However, we prevail. Our stories are important for the world to see, not just for the fragile comforts of public acclaim but to illustrate the resilience and brilliance of Black women. As author Stephanie Power-Carter states in “Seeing through Silence: The Memory of We, “‘ remembering is essential to navigating the silences and tensions that the gaze of whiteness holds .

‘This act of remembering is crucial as a foundation for future generations to build upon their own ‘becoming .’It’s in this spirit of remembering and celebrating that Alice Randall’s response to Beyoncé’s arrival in country music resonates so deeply. ‘I almost wanna cry. I wanted to see a Black woman get to the top of the country charts. I can retire now,’.

So, while we all enjoy the full unveiling of Beyoncé’s new album, I am certain that her return to country music will make an undeniable impact on generations past, present, and future. Her story mirrors that of countless Black women who face the colossal task of reclaiming legacies denied. This struggle is not unique to women in country music. It resonates with Black women across multiple fields who confront spaces that have systematically undervalued their contributions. These structures attempt to erase their work and ignore their impact, hiding their stories from future generations.

In order to recognize and celebrate the achievements of Black women demands a radical upheaval of these practices and established footholds. This is how we disrupt the Black Girlboss Paradox and ensure that we preserve the legacies of Black women. If I were to bet on anyone ‘winning this hand,’ I’d place my bets on Queen B. Truth be told, my wager has always been — and will always be — on Black women to make space to remember and celebrate other Black women. The fight for visibility and acknowledgment of Black women in country music mirrors a global struggle for equity and representation for Black women in all walks of life; it transcends both genre and industry.

Beyoncé’s country foray is a clarion call, urging us to take part actively in the broader movement towards dismantling systemic inequities, not just listen. It’s a reminder that the essence of country music, like all cultural legacies, thrives when it fully embraces the diverse voices that shape it and, as a result, tells a more complete story. For now, I’m grateful to Beyonce for reminding us with every note she sings that she’s not just performing country — she’s reclaiming it. She is returning country music to its roots and asserting the rightful place of Black women within a genre where their contributions should not just be seen and heard but remembered.

Kimberly Bryant is the founder of both Black Girls CODE and ASCEND Ventures. She is also a Public Voices fellow on Advancing the Rights of Women and Girls with The OpEd Project and Equality Now.