By Esther Claudette Gittens

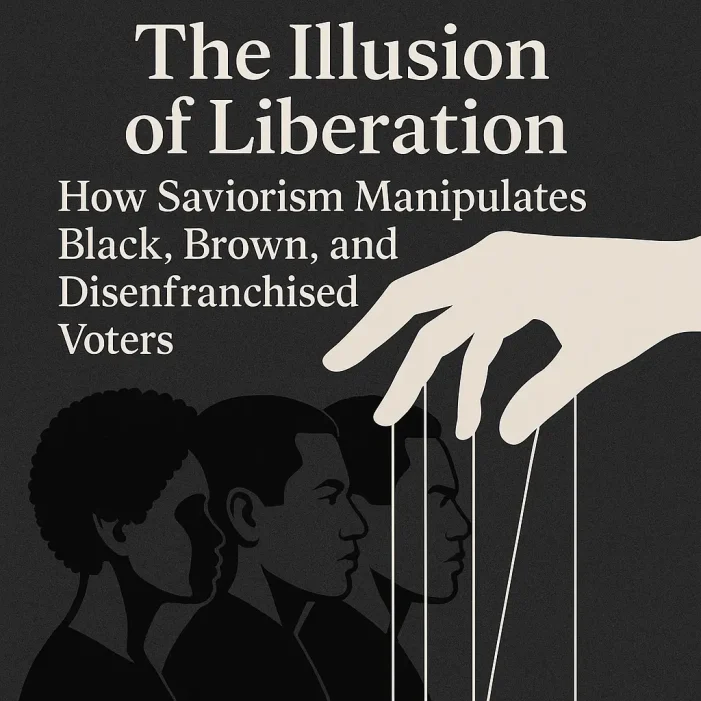

The political landscape, particularly in diverse democracies, is often characterized by a complex interplay of power, representation, and voter mobilization. Within this intricate web, a persistent and insidious phenomenon known as “saviorism” frequently emerges, particularly from white politicians and often within the Democratic party, aiming to capture the votes of Black, Brown, and other disenfranchised communities. This article will delve into the theory of political saviorism, examining its historical roots, its manifestations, and the detrimental impact it has on the agency and empowerment of the very communities it purports to “save.”

Saviorism, at its core, is the belief, often implicit, that a dominant group or individual has a responsibility to “save” or “uplift” marginalized groups, based on an underlying assumption of their own superiority and the perceived inability of the marginalized to help themselves. In the political arena, this translates into a narrative where politicians position themselves as the benevolent champions of disadvantaged communities, offering solutions without genuinely empowering these communities to define their own needs or lead their own liberation. This trope is not new; its roots can be traced to colonialist ideologies, epitomized by Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden,” which posited a moral obligation for white Europeans to civilize and govern non-white populations.

In contemporary American politics, this “white savior complex” manifests in various forms. White politicians, particularly those from the Democratic party, often adopt a rhetorical stance that emphasizes their empathy for and commitment to racial justice and equity. They attend community events, make pronouncements about systemic racism, and advocate for policies that, on the surface, appear to address the disparities faced by Black, Brown, and other marginalized groups. However, the critique of saviorism lies in the approach and underlying assumptions of these efforts.

One key characteristic of political saviorism is the tendency to offer solutions that are top-down, devised without genuine, sustained input from the communities they intend to serve. This can lead to policies that are well-intentioned but ultimately ineffective or even harmful, as they fail to address the nuanced realities and priorities of the affected populations. For instance, a politician might champion a new educational program for inner-city schools without consulting with Black and Brown parents, educators, and community leaders about what they believe are the most pressing issues. This approach disempowers these communities by denying their agency and expertise in their own lived experiences.

Furthermore, saviorism often reduces complex systemic issues to simplistic narratives, framing the problems of marginalized communities as needing external intervention rather than recognizing the inherent strength, resilience, and wisdom within these communities. This narrative can inadvertently perpetuate harmful stereotypes, implying that Black and Brown communities are inherently helpless or lacking in the capacity for self-determination. When politicians cast themselves as the sole arbiters of progress, they reinforce a power dynamic where the marginalized remain reliant on the benevolence of the dominant group, rather than being seen as powerful agents of change in their own right.

The Democratic party, despite its stated commitment to diversity and inclusion, is not immune to the pitfalls of political saviorism. Indeed, some critics argue that the party’s consistent reliance on the Black vote, coupled with a perceived lack of substantive policy change specifically favoring Black interests, is a manifestation of this dynamic. While Black voters consistently turn out at high rates for Democratic candidates, there’s a growing sentiment among some that their loyalty is taken for granted, and that the party often prioritizes other agendas once in power. This can breed cynicism and disillusionment, as voters feel that their concerns are acknowledged during election cycles but not genuinely addressed afterward.

The impact of this saviuristic approach on disenfranchised voters is profound. It can create a cycle of dependency, where communities are led to believe that their only path to progress is through supporting the “savior” politician or party. This can discourage self-organizing, grassroots activism, and the development of independent political power within these communities. When the focus is on being “saved” rather than on self-emancipation, the potential for truly transformative change is diminished.

Moreover, the performative aspects of political saviorism can be particularly frustrating. Grand gestures, emotional speeches, and photo opportunities in Black and Brown neighborhoods, while seemingly positive, can feel superficial when not backed by sustained, authentic engagement and concrete policy outcomes that genuinely shift power dynamics. This can contribute to voter apathy and disengagement, as marginalized voters grow weary of being a political prop rather than a true partner in governance.

To move beyond saviorism, a fundamental shift in political engagement is required. This involves:

- Authentic Listening and Collaboration: Politicians and parties must genuinely listen to and prioritize the voices, experiences, and policy demands of Black, Brown, and disenfranchised communities. This means moving beyond tokenistic consultations to deeply embedded, community-led initiatives.

- Empowerment over Paternalism: The focus should be on empowering communities to build their own political power, advocating for policies that enable self-determination and dismantle systemic barriers, rather than simply providing aid.

- Investing in Grassroots Leadership: Supporting and investing in existing Black, Brown, and disenfranchised community leaders and organizations is crucial, recognizing their invaluable expertise and historical work.

- Accountability and Tangible Results: Promises made during election campaigns must be met with measurable and impactful policy changes that demonstrably improve the lives of marginalized communities.

- Challenging Implicit Bias: Politicians and parties must critically examine their own implicit biases and assumptions that may underpin saviuristic tendencies.

In conclusion, the theory of saviorism in politics, especially when employed by white politicians and within the Democratic party, presents a significant hurdle to genuine liberation and empowerment for Black, Brown, and disenfranchised voters. While the intention may sometimes be good, the underlying assumptions and practices of saviorism can perpetuate dependency, undermine agency, and ultimately hinder the very progress it claims to foster. Moving forward, a paradigm shift is needed – one that prioritizes authentic partnership, community-led solutions, and a deep respect for the inherent power and wisdom of all communities in shaping their own destinies. Only then can the illusion of liberation give way to its true realization.